Introduction to SQL

What is SQL?

SQL, or Structured Query Language, is a language designed to allow both technical and non-technical users query, manipulate, and transform data from a relational database. And due to its simplicity, SQL databases provide safe and scalable storage for millions of websites and mobile applications.

- Did you know?

There are many popular SQL databases including SQLite, MySQL, Postgres, Oracle and Microsoft SQL Server. All of them support the common SQL language standard, which is what this site will be teaching, but each implementation can differ in the additional features and storage types it supports.

- Relational databases

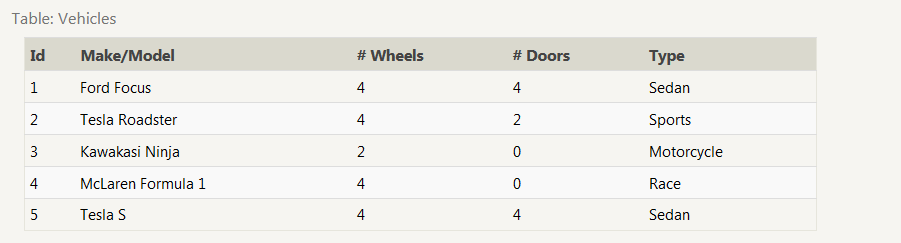

Before learning the SQL syntax, it’s important to have a model for what a relational database actually is. A relational database represents a collection of related (two-dimensional) tables. Each of the tables are similar to an Excel spreadsheet, with a fixed number of named columns (the attributes or properties of the table) and any number of rows of data.

For example, if the Department of Motor Vehicles had a database, you might find a table containing all the known vehicles that people in the state are driving. This table might need to store the model name, type, number of wheels, and number of doors of each vehicle for example.

- In such a database, you might find additional related tables containing information such as a list of all registered drivers in the state, the types of driving licenses that can be granted, or even driving violations for each driver.

By learning SQL, the goal is to learn how to answer specific questions about this data, like “What types of vehicles are on the road have less than four wheels?”, or “How many models of cars does Tesla produce?”, to help us make better decisions down the road.

SELECT queries 101

To retrieve data from a SQL database, we need to write SELECT statements, which are often colloquially refered to as queries. A query in itself is just a statement which declares what data we are looking for, where to find it in the database, and optionally, how to transform it before it is returned. It has a specific syntax though, which is what we are going to learn in the following exercises.

As we mentioned in the introduction, you can think of a table in SQL as a type of an entity (ie. Dogs), and each row in that table as a specific instance of that type (ie. A pug, a beagle, a different colored pug, etc). This means that the columns would then represent the common properties shared by all instances of that entity (ie. Color of fur, length of tail, etc).

And given a table of data, the most basic query we could write would be one that selects for a couple columns (properties) of the table with all the rows (instances).

Select query for a specific columns:

SELECT column, another_column, …

FROM mytable;

- The result of this query will be a two-dimensional set of rows and columns, effectively a copy of the table, but only with the columns that we requested.

If we want to retrieve absolutely all the columns of data from a table, we can then use the asterisk (*) shorthand in place of listing all the column names individually.

Select query for all columns:

SELECT *

FROM mytable;

- This query, in particular, is really useful because it’s a simple way to inspect a table by dumping all the data at once.

Queries with constraints

Now we know how to select for specific columns of data from a table, but if you had a table with a hundred million rows of data, reading through all the rows would be inefficient and perhaps even impossible.

In order to filter certain results from being returned, we need to use a WHERE clause in the query. The clause is applied to each row of data by checking specific column values to determine whether it should be included in the results or not.

Select query with constraints:

SELECT column, another_column, …

FROM mytable

WHERE condition

AND/OR another_condition

AND/OR …;

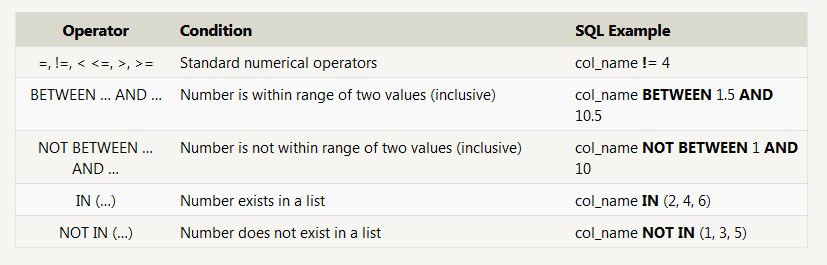

- More complex clauses can be constructed by joining numerous AND or OR logical keywords (ie. num_wheels >= 4 AND doors <= 2). And below are some useful operators that you can use for numerical data (ie. integer or floating point):

-

In addition to making the results more manageable to understand, writing clauses to constrain the set of rows returned also allows the query to run faster due to the reduction in unnecessary data being returned.

-

Did you know?

As you might have noticed by now, SQL doesn’t require you to write the keywords all capitalized, but as a convention, it helps people distinguish SQL keywords from column and tables names, and makes the query easier to read.

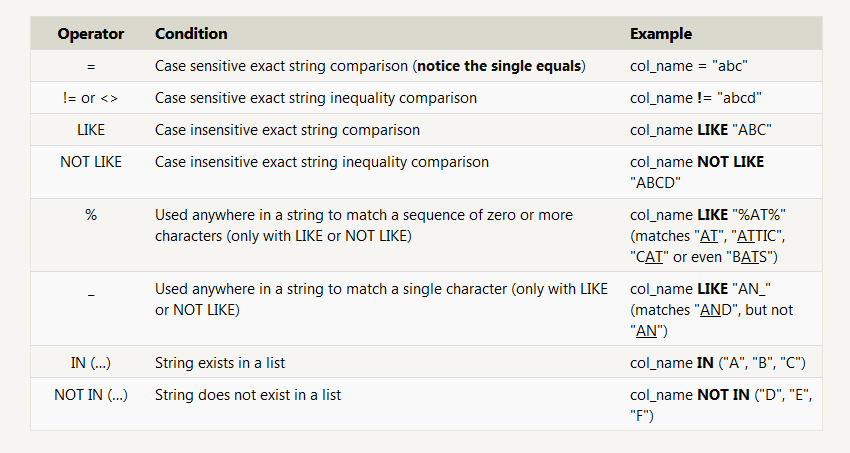

- When writing WHERE clauses with columns containing text data, SQL supports a number of useful operators to do things like case-insensitive string comparison and wildcard pattern matching. We show a few common text-data specific operators below:

- Did you know?

All strings must be quoted so that the query parser can distinguish words in the string from SQL keywords.

- We should note that while most database implementations are quite efficient when using these operators, full-text search is best left to dedicated libraries like Apache Lucene or Sphinx. These libraries are designed specifically to do full text search, and as a result are more efficient and can support a wider variety of search features including internationalization and advanced queries.

Filtering and sorting Query results

Even though the data in a database may be unique, the results of any particular query may not be – take our Movies table for example, many different movies can be released the same year. In such cases, SQL provides a convenient way to discard rows that have a duplicate column value by using the DISTINCT keyword.

Select query with unique results:

SELECT DISTINCT column, another_column, …

FROM mytable

WHERE condition(s);

-

Since the DISTINCT keyword will blindly remove duplicate rows, we will learn in a future lesson how to discard duplicates based on specific columns using grouping and the GROUP BY clause.

-

Ordering results

Unlike our neatly ordered table in the last few lessons, most data in real databases are added in no particular column order. As a result, it can be difficult to read through and understand the results of a query as the size of a table increases to thousands or even millions rows.

To help with this, SQL provides a way to sort your results by a given column in ascending or descending order using the ORDER BY clause.

Select query with ordered results:

SELECT column, another_column, …

FROM mytable

WHERE condition(s)

ORDER BY column ASC/DESC;

-

When an ORDER BY clause is specified, each row is sorted alpha-numerically based on the specified column’s value. In some databases, you can also specify a collation to better sort data containing international text.

-

Limiting results to a subset

Another clause which is commonly used with the ORDER BY clause are the LIMIT and OFFSET clauses, which are a useful optimization to indicate to the database the subset of the results you care about. The LIMIT will reduce the number of rows to return, and the optional OFFSET will specify where to begin counting the number rows from.

Select query with limited rows:

SELECT column, another_column, …

FROM mytable

WHERE condition(s)

ORDER BY column ASC/DESC

LIMIT num_limit OFFSET num_offset;

If you think about websites like Reddit or Pinterest, the front page is a list of links sorted by popularity and time, and each subsequent page can be represented by sets of links at different offsets in the database. Using these clauses, the database can then execute queries faster and more efficiently by processing and returning only the requested content.

- Did you know?

If you are curious about when the LIMIT and OFFSET are applied relative to the other parts of a query, they are generally done last after the other clauses have been applied. We’ll touch more on this in Lesson 12: Order of execution after introducting a few more parts of the query.

References:

-

Learn SQL with simple, interactive exercises. Check it out

-

SQL practice on W3Schools Check it out

-

Learn SQL with simple, interactive exercises. Read the full article here

-

SQL cheatsheet Check it out